WAGE Initiatives and Male Engagement Strategies

Approaches to Male Engagement in Women’s Empowerment Programs

How and why are women disempowered?

The degree to which people have agency over their own lives and exercise bodily autonomy is very much determined by their gender, sexual orientation, and socio-cultural norms. Socio-cultural norms heavily influence how human beings organize their lives, think about gender roles, and assign power, value and status. Power in any given society is derived from privilege. In today’s modern world, patriarchal power structures are dominant and assign men and boys greater value and privilege. This is evident in the systemic structural, relational, material, and personal barriers women face that prevent them from fully participating in political, economic, and civic life. These barriers exist at and are felt across society and multiple levels of analysis including individual, household, community, organizational, and institutional. Some of the ways women experience these barriers include the normalization of their exclusion, oppression, exploitation, victimization due to violence, and subordinate roles they are assigned.

WAGE male engagement approaches within women’s empowerment programs

The Women and Girls Empowered (WAGE) Global Consortium examines these barriers across 10 initiatives throughout 15 countries. Our approach is gender transformative and utilizes male engagement to question harmful patriarchal socio-cultural norms, leverage male champions to increase male buy-in for women’s empowerment, mitigate backlash to women’s empowerment, and to effect change and perceptions around harmful gender norms.

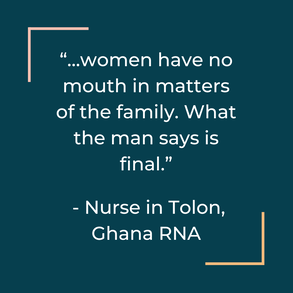

WAGE initiatives are grounded and informed by our Gender and Inclusion Analysis (G&IA) and Rapid Needs and Barriers Assessments. Our rapid needs assessments (RNA) found that microfinance institutions (MFIs) generally do not make the link or have the tools to address gender-based violence (GBV) as an unintended consequence of women’s economic empowerment (WEE). For example, in the barriers assessment for El Salvador, interviewed MFIs “acknowledged that [they] do not yet have well-developed gender policies, strategies, or tools that would help them prevent or mitigate the potential negative consequences of women’s economic empowerment programs, such as increased levels of VAW.”[1] Our assessment findings validate well established research on the WEE/GBV nexus that has found a woman’s increased income often shifts the power dynamics at the household level. This increase challenges prevailing notions of masculinity that designate men as primary bread winners, principal authority within the home, and final decision makers over the use of income.[2] In some contexts, men perceive increases in a woman’s income as a loss of power, which in turn can cause some men to justify preventing women from making independent decisions about their income.[3] In extreme cases, men can resort to violence to “reclaim” their power. Unfortunately, in many societies, violence towards women is seen as acceptable and normalized as discipline and a way to “prove” one’s masculinity and authority, keep order and structure in the home.[4]

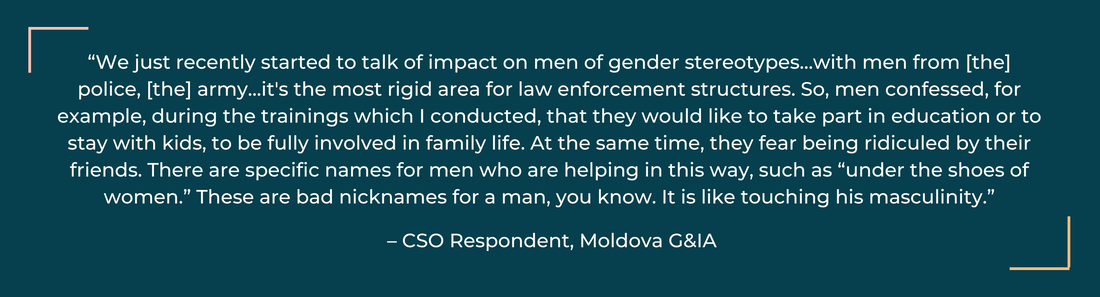

There is growing recognition that patriarchal norms also harm men. For example, men are perceived as weak if they share joint decision making with their partners, ask for help, or express emotional vulnerability.[5] This expectation contributes to decisions that can impact families negatively, and poor physical and mental health outcomes for men, including substance abuse. The value of a man is often equated to the amount of money he earns. Enormous pressure stems from being seen as the primary breadwinner. This pressure can be immense in contexts where economic opportunities are scarce. All of these expectations put women at risk of GBV at the hands of their intimate partners.

The degree to which people have agency over their own lives and exercise bodily autonomy is very much determined by their gender, sexual orientation, and socio-cultural norms. Socio-cultural norms heavily influence how human beings organize their lives, think about gender roles, and assign power, value and status. Power in any given society is derived from privilege. In today’s modern world, patriarchal power structures are dominant and assign men and boys greater value and privilege. This is evident in the systemic structural, relational, material, and personal barriers women face that prevent them from fully participating in political, economic, and civic life. These barriers exist at and are felt across society and multiple levels of analysis including individual, household, community, organizational, and institutional. Some of the ways women experience these barriers include the normalization of their exclusion, oppression, exploitation, victimization due to violence, and subordinate roles they are assigned.

WAGE male engagement approaches within women’s empowerment programs

The Women and Girls Empowered (WAGE) Global Consortium examines these barriers across 10 initiatives throughout 15 countries. Our approach is gender transformative and utilizes male engagement to question harmful patriarchal socio-cultural norms, leverage male champions to increase male buy-in for women’s empowerment, mitigate backlash to women’s empowerment, and to effect change and perceptions around harmful gender norms.

WAGE initiatives are grounded and informed by our Gender and Inclusion Analysis (G&IA) and Rapid Needs and Barriers Assessments. Our rapid needs assessments (RNA) found that microfinance institutions (MFIs) generally do not make the link or have the tools to address gender-based violence (GBV) as an unintended consequence of women’s economic empowerment (WEE). For example, in the barriers assessment for El Salvador, interviewed MFIs “acknowledged that [they] do not yet have well-developed gender policies, strategies, or tools that would help them prevent or mitigate the potential negative consequences of women’s economic empowerment programs, such as increased levels of VAW.”[1] Our assessment findings validate well established research on the WEE/GBV nexus that has found a woman’s increased income often shifts the power dynamics at the household level. This increase challenges prevailing notions of masculinity that designate men as primary bread winners, principal authority within the home, and final decision makers over the use of income.[2] In some contexts, men perceive increases in a woman’s income as a loss of power, which in turn can cause some men to justify preventing women from making independent decisions about their income.[3] In extreme cases, men can resort to violence to “reclaim” their power. Unfortunately, in many societies, violence towards women is seen as acceptable and normalized as discipline and a way to “prove” one’s masculinity and authority, keep order and structure in the home.[4]

There is growing recognition that patriarchal norms also harm men. For example, men are perceived as weak if they share joint decision making with their partners, ask for help, or express emotional vulnerability.[5] This expectation contributes to decisions that can impact families negatively, and poor physical and mental health outcomes for men, including substance abuse. The value of a man is often equated to the amount of money he earns. Enormous pressure stems from being seen as the primary breadwinner. This pressure can be immense in contexts where economic opportunities are scarce. All of these expectations put women at risk of GBV at the hands of their intimate partners.

Recognizing these impacts, in Eswatini, WAGE partnered with Kwakha Indvodza (KI), a CSO working with men and boys to address the root causes of GBV and promote positive masculinity. Through our partnership, WAGE reached over 117,000 people via Facebook through KI’s #Me4U (mental health) campaign. The #Me4U campaign is a series of live chats or “episodes” that provide a space to discuss pressing issues and misconceptions experienced by young men in Eswatini, including GBV. KI’s Babe Locotfo or Good Father Campaign educates young fathers about the positive impacts of being a present and involved father, including closer bonds to their children, family stability, stronger communities, and improved socio-economic opportunities. It also networks new fathers, allowing them to form a community. Through the campaign, new fathers are able to embrace positive masculinity which is essential to reducing the risk of GBV.

In Ghana, WAGE is engaging male spouses to obtain buy-in for their wives to start and sustain their digital financial service (DFS)/mobile-money businesses. WAGE has seen enthusiastic participation on the part of male spouses who are eager to support their wives’ DFS business because of the financial benefits it provides to their families and communities. Orientation sessions for DFS agents and their spouses focused on what the mobile-money business model is and ways men can support their wives in their new roles. WAGE facilitated open discussions among men where they talked about giving their wives more independence and reducing the level of household responsibilities they have, thus allowing them to focus on their business. Women DFS agents are also providing GBV prevention education to their communities and information about GBV support services. Because GBV is seen as a private family matter in Ghana, WAGE took this into account in safeguarding DFS agents. WAGE local CSO partners met with community gatekeepers, including religious and community leaders, to explain these GBV prevention interventions. This was a necessary measure the program took to ensure the DFS agents were not perceived as meddling in the private matters of families within their communities. That kind of perception presents a high risk of violence/harm to the DFS agents.

WAGE programming in Sri Lanka secured male support for WEE in ways that were unintended in some cases and also through intentional program design. Because of COVID-19 lockdowns, the program delivered business, financial, and digital training virtually. This exposed male spouses to the curriculum and peeked interest and support for their wives learning about ways they could begin engaging in economic activity. The program identified influential male allies for WEE at the community and district levels who worked with local women political, economic, CSO leaders to establish community level WILL (women in learning and leadership) Clubs. WAGE also utilized highly collaborative and participatory approaches to cultivate trust and shared ownership of the collaborative action plans these Clubs developed to advance WEE at the community level. For instance, the agenda and priorities of each Club were determined by its members.

The WAGE initiative in El Salvador and Honduras raised the awareness of WAGE local partner MFIs about the interplay between gender, power, and conflict through a series of trainings.[6] Close to 70 percent of training participants were male, and in the training male participants reflected on their masculinity and discussed the benefits of gender equality. For many male MFI staff, this was eye opening and an initial first step to building individual awareness about their own unconscious bias and how that plays out in their households, workplaces, and broader society. Women staff also gained similar awareness about the impacts of harmful gender norms at the household and workplace levels, and also within broader society.

In Timor-Leste, WAGE recently piloted intra-household dialogues (IHDs). Participants included households that had women clients of WAGE partner MFIs. The dialogues took couples through a process of self-reflection using a range of facilitation techniques, including role play, to explore their understanding of gender, roles ascribed to men and women, and how these roles hindered women’s entrepreneurship. The dialogues also discussed the benefits of women’s economic empowerment at the household level. The IHDs gave husbands and wives the opportunity to “step into each other’s world” and work collaboratively to develop a joint plan for shared household responsibility including income generation.

To advance our Learning Agenda, WAGE will be producing a range of learning products and publications that look at changes in perceptions on harmful gender norms. Stay tuned for these and other learnings including our upcoming blog post on lessons learned from male engagement activities in women’s empowerment programming.

[1] “Women’s Economic Empowerment in El Salvador: Barriers, Opportunities, and a Path Forward”, pg. 49, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/roli/misc/elsalvador-women-economic-empowerment-barriers-opportunities-path-forward-full-10-2019.pdf. See the following assessments for additional related findings: “Women’s Economic Empowerment in Honduras: Barriers, Opportunities, and a Path Forward”, pg. 41, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/roli/misc/honduras-women-economic-empowerment-barriers-opportunities-path-forward-full-10-2019.pdf, “Preliminary Gender and Inclusion Analysis for Timor-Leste”, pg. 10, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/roli/wage/gender-inclusiontimor.pdf.

[2] “Rapid Needs Assessment: Ghana”, p. 18 https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/roli/wage/wage-ghana-rapid-needs-assessment-2022.pdf

[3] “Women’s Economic Empowerment in El Salvador: Barriers, Opportunities, and a Path Forward”, pg. i https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/roli/misc/elsalvador-women-economic-empowerment-barriers-opportunities-path-forward-full-10-2019.pdf

[4] “Women’s Entrepreneurship in Timor Leste: An Assessment of Opportunities, Barriers and A Path Forward”, p. 10 https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/roli/timorleste/wagetimorleste.pdf

[5] “Moldova Gender and Inclusion Analysis”, pg. 10, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/roli/wage/gender-inclusionmoldova.pdf.

[6] These trainings and our male engagement strategies in El Salvador and Honduras are reinforced by organizational strengthening and linkage interventions designed to safeguard women from GBV as a result of WEE. More information on these activities can be found here: https://www.wageglobal.org/rbi-kiva-loan-matching.html.

WAGE programming in Sri Lanka secured male support for WEE in ways that were unintended in some cases and also through intentional program design. Because of COVID-19 lockdowns, the program delivered business, financial, and digital training virtually. This exposed male spouses to the curriculum and peeked interest and support for their wives learning about ways they could begin engaging in economic activity. The program identified influential male allies for WEE at the community and district levels who worked with local women political, economic, CSO leaders to establish community level WILL (women in learning and leadership) Clubs. WAGE also utilized highly collaborative and participatory approaches to cultivate trust and shared ownership of the collaborative action plans these Clubs developed to advance WEE at the community level. For instance, the agenda and priorities of each Club were determined by its members.

The WAGE initiative in El Salvador and Honduras raised the awareness of WAGE local partner MFIs about the interplay between gender, power, and conflict through a series of trainings.[6] Close to 70 percent of training participants were male, and in the training male participants reflected on their masculinity and discussed the benefits of gender equality. For many male MFI staff, this was eye opening and an initial first step to building individual awareness about their own unconscious bias and how that plays out in their households, workplaces, and broader society. Women staff also gained similar awareness about the impacts of harmful gender norms at the household and workplace levels, and also within broader society.

In Timor-Leste, WAGE recently piloted intra-household dialogues (IHDs). Participants included households that had women clients of WAGE partner MFIs. The dialogues took couples through a process of self-reflection using a range of facilitation techniques, including role play, to explore their understanding of gender, roles ascribed to men and women, and how these roles hindered women’s entrepreneurship. The dialogues also discussed the benefits of women’s economic empowerment at the household level. The IHDs gave husbands and wives the opportunity to “step into each other’s world” and work collaboratively to develop a joint plan for shared household responsibility including income generation.

To advance our Learning Agenda, WAGE will be producing a range of learning products and publications that look at changes in perceptions on harmful gender norms. Stay tuned for these and other learnings including our upcoming blog post on lessons learned from male engagement activities in women’s empowerment programming.

[1] “Women’s Economic Empowerment in El Salvador: Barriers, Opportunities, and a Path Forward”, pg. 49, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/roli/misc/elsalvador-women-economic-empowerment-barriers-opportunities-path-forward-full-10-2019.pdf. See the following assessments for additional related findings: “Women’s Economic Empowerment in Honduras: Barriers, Opportunities, and a Path Forward”, pg. 41, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/roli/misc/honduras-women-economic-empowerment-barriers-opportunities-path-forward-full-10-2019.pdf, “Preliminary Gender and Inclusion Analysis for Timor-Leste”, pg. 10, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/roli/wage/gender-inclusiontimor.pdf.

[2] “Rapid Needs Assessment: Ghana”, p. 18 https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/roli/wage/wage-ghana-rapid-needs-assessment-2022.pdf

[3] “Women’s Economic Empowerment in El Salvador: Barriers, Opportunities, and a Path Forward”, pg. i https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/roli/misc/elsalvador-women-economic-empowerment-barriers-opportunities-path-forward-full-10-2019.pdf

[4] “Women’s Entrepreneurship in Timor Leste: An Assessment of Opportunities, Barriers and A Path Forward”, p. 10 https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/roli/timorleste/wagetimorleste.pdf

[5] “Moldova Gender and Inclusion Analysis”, pg. 10, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/roli/wage/gender-inclusionmoldova.pdf.

[6] These trainings and our male engagement strategies in El Salvador and Honduras are reinforced by organizational strengthening and linkage interventions designed to safeguard women from GBV as a result of WEE. More information on these activities can be found here: https://www.wageglobal.org/rbi-kiva-loan-matching.html.

Posted on May 1, 2023.

About the Author

Muthoni Kamuyu-Ojuolo, Program Director, Women and Girls Empowered (WAGE), has close to two decades in the field of international development with regional expertise in Africa. Over the course of her career, she has focused on democracy and governance, women’s empowerment, and rule of law. Prior to joining ABA ROLI, Muthoni served as the Director for Africa and Accountable Governance at PartnersGlobal, where she led a range of rule of law programs designed to improve inter-agency coordination on criminal justice reform. During her 10 year tenure at the National Democratic Institute (NDI), she designed and managed political inclusion programs that increased the participation of women, youth, and people with disabilities in elections and prepared women to run for elected office. As the lead for NDI’s extractive industry governance programs, she drove consensus among government, corporations, and communities to secure the environmental rights and protections of mining and oil communities and in particular women living in these communities. At the Center for International Private Enterprise, Muthoni’s work focused on organizing informal sector workers for joint action to advance policy, legislative, and regulatory priorities that would enable them to enter the formal economy. Muthoni has led and managed programs in several African countries including The Gambia, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, South Africa and Zambia to name a few. She earned a BA in International Business with a concentration in Finance from Eastern Michigan University and is a proud alum of Howard University where she earned a MA in African Studies with a concentration in Conflict Resolution.

About the Author

Muthoni Kamuyu-Ojuolo, Program Director, Women and Girls Empowered (WAGE), has close to two decades in the field of international development with regional expertise in Africa. Over the course of her career, she has focused on democracy and governance, women’s empowerment, and rule of law. Prior to joining ABA ROLI, Muthoni served as the Director for Africa and Accountable Governance at PartnersGlobal, where she led a range of rule of law programs designed to improve inter-agency coordination on criminal justice reform. During her 10 year tenure at the National Democratic Institute (NDI), she designed and managed political inclusion programs that increased the participation of women, youth, and people with disabilities in elections and prepared women to run for elected office. As the lead for NDI’s extractive industry governance programs, she drove consensus among government, corporations, and communities to secure the environmental rights and protections of mining and oil communities and in particular women living in these communities. At the Center for International Private Enterprise, Muthoni’s work focused on organizing informal sector workers for joint action to advance policy, legislative, and regulatory priorities that would enable them to enter the formal economy. Muthoni has led and managed programs in several African countries including The Gambia, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, South Africa and Zambia to name a few. She earned a BA in International Business with a concentration in Finance from Eastern Michigan University and is a proud alum of Howard University where she earned a MA in African Studies with a concentration in Conflict Resolution.

|

|

*Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Government.

Women and Girls Empowered (WAGE) is a global consortium to advance the status of women and girls, led by the American Bar Association Rule of Law Initiative (ABA ROLI) in close partnership with the Center for International Private Enterprise, Grameen Foundation, and Search for Common Ground. WAGE works to strengthen the capacity of private sector organizations (PSOs) and civil society organizations (CSOs) in target countries to improve the prevention of and response to gender-based violence (GBV); advance the women, peace, and security (WPS) agenda; and support women’s economic empowerment (WEE). In this context, WAGE provides direct assistance to women and girls, including information, resources, and services they need to succeed as active and equal participants in the global economy. WAGE also engages in collaborative research and learning to build a body of evidence on relevant promising practices in these thematic areas. To account for the deeply interconnected nature of women’s and girls’ experiences, WAGE’s initiatives employ approaches that are highly collaborative, integrated, and inclusive. WAGE is funded by the U.S. Department of State Secretary’s Office of Global Women’s Issues.

Women and Girls Empowered (WAGE) is a global consortium to advance the status of women and girls, led by the American Bar Association Rule of Law Initiative (ABA ROLI) in close partnership with the Center for International Private Enterprise, Grameen Foundation, and Search for Common Ground. WAGE works to strengthen the capacity of private sector organizations (PSOs) and civil society organizations (CSOs) in target countries to improve the prevention of and response to gender-based violence (GBV); advance the women, peace, and security (WPS) agenda; and support women’s economic empowerment (WEE). In this context, WAGE provides direct assistance to women and girls, including information, resources, and services they need to succeed as active and equal participants in the global economy. WAGE also engages in collaborative research and learning to build a body of evidence on relevant promising practices in these thematic areas. To account for the deeply interconnected nature of women’s and girls’ experiences, WAGE’s initiatives employ approaches that are highly collaborative, integrated, and inclusive. WAGE is funded by the U.S. Department of State Secretary’s Office of Global Women’s Issues.